Dolphinvest Global Asset Managers Barometer

Asset managers in the line of fire

Central banks should be independent of politics. This is a generally accepted claim that usually only autocrats undermine in a blatant way. Fighting inflation is commonly considered the main task of all central banks, often paired with the task of maintaining financial and currency stability, while some would also like to include economic stimulus and measures to combat recessions. Central banks are indispensable for all economic activity, as they alone have the right to issue bank notes and coins, meaning to create cash,

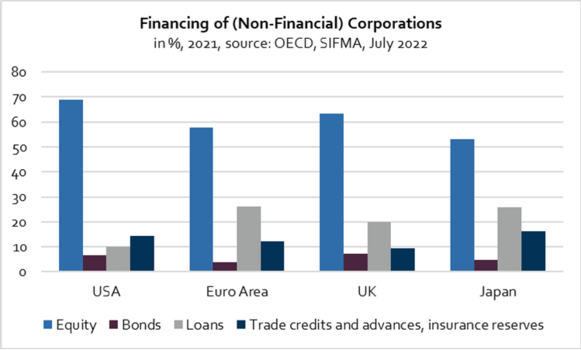

while they are also responsible for the management of currency reserves and set the benchmark interest rates for commercial banks in their respective countries. Just like central banks, commercial banks are essential to the economic functioning of societies, but occasionally they also cause major economic crises. Companies, in turn, satisfy their capital needs through banks, but even more so in the capital markets.

The independence of central banks has never had a life of celibacy. On the contrary, the recruitment of personnel relies on a menage à trois of central banks, government and capital markets. Among the prominent examples is Christine Lagarde, who currently heads the European Central Bank after holding positions at McKinsey and as France’s finance minister. Mario Draghi, erstwhile investment banker at Goldman Sachs and former head of Italy’s central bank, became Italian prime minister after his time as ECB president. Mark Carney, once an investment banker at Goldman Sachs and head of Canada’s central bank, followed his tenure as governor of the Bank of England with a posting as vice chairman of Brookfield Asset Management, where he is responsible for sustainable investing – a field that Christine Lagarde considers as a new area of responsibility for the ECB. After only four months in office, she announced in February 2020 her climate policy aspirations and subsequently implemented the politicisation of the ECB in an expeditious way and without much public debate. On the ECB website, it now officially says: “We are firmly committed to doing our part to address climate change, within our mandate.”

Whether the switching of positions between central banks, government and capital markets runs contrary to the independence requirement for central banks, is anyone’s guess. But what it means when cooperation between the three areas doesn’t work at all recently became all too clear to the United Kingdom’s pension funds and future beneficiaries of company retirement schemes – a drama that The Economist considered worthy of the headline “How not to run a country” on its cover.

What happened? Shortly after the Bank of England raised interest rates on 22 September, the UK’s Chancellor of the Exchequer announced large-scale, debt-financed tax cuts that also threatened social unrest. The central bank’s interest rate hike and the government’s planned debt increase reinforced each other in their effect. UK bonds and the British pound sterling (GBP) suffered a dramatic collapse. However, the immediate publicity-grabbing effect was stress in the system of any defined-benefit pension funds that use liability-driven investment (LDI) strategies to hedge the future payments of employers to company pension holders. LDI strategies are hedging strategies with bonds as collateral, so they react to changes in interest rates. The sudden price slump in bonds triggered margin calls on the affected pension funds – which can be freely interpreted here as “Your money or your life!” in view of the effect. The fund managers were promptly accused of having failed to adequately explain the interest-rate risks of LDI strategies to their clients. The Bank of England felt compelled to intervene with a rescue package amounting to GBP 65 billion by temporarily buying up long-dated bonds and pointing to the potential risks for the UK’s financial stability. Passing the buck, but luckily not a black swan event. But this was reason enough for the International Monetary Fund to admonish the UK government openly – something that usually only governments of less developed nations have to endure.

The UK fund industry recorded net outflows of around GBP 13 billion in September, the largest monthly outflows in at least 10 years, including in March 2020, when GBP 7.3 billion was withdrawn from UK investment funds due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The returns on index funds with UK government bonds (“gilts”) were worst affected by the crisis, falling 9.3% on average in the last week of September. But UK equity funds were also losers, dropping 5.9% on average (for small and mid-caps) and 5.2% (for all companies). By comparison, the equities of publicly listed UK asset managers fell by 10.85% on average in September, with an average decline of 7.38% in the last week of September alone (source: Dolphinvest, Refinitiv, in GBP).

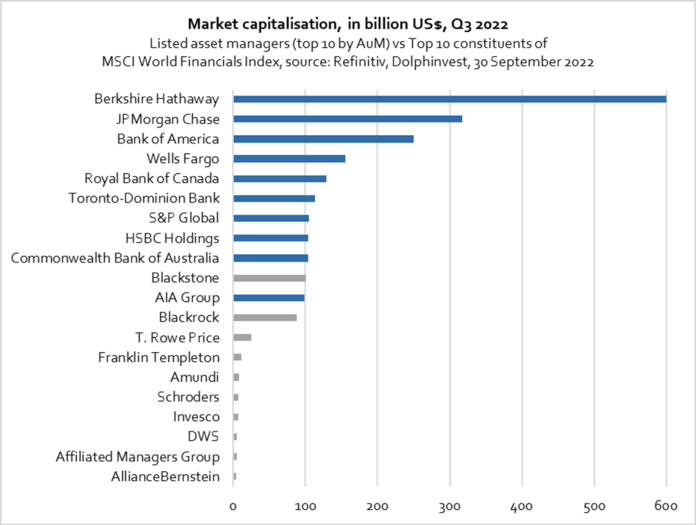

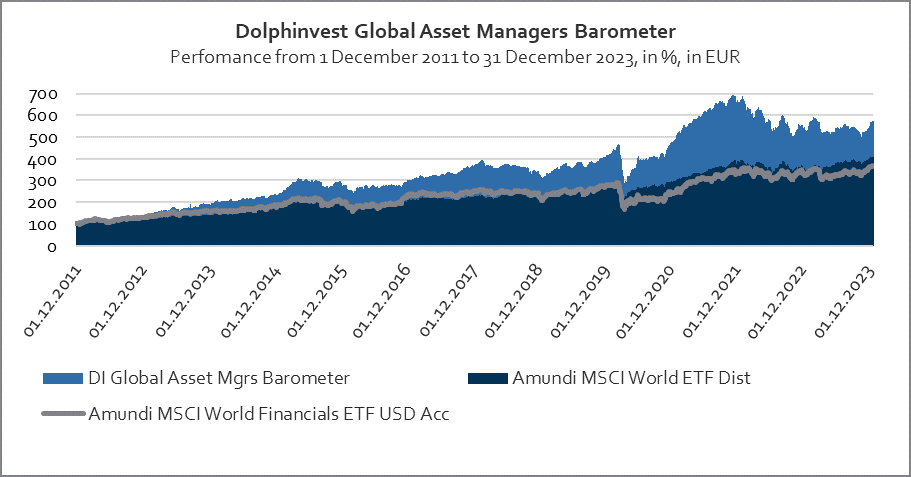

While they are a sub-sector of the financial industry and very important for the functioning of global capital markets, asset managers nevertheless are rarely in the public spotlight as much as they are now in the United Kingdom. Very few of them are publicly listed – meaning transparent to the public – with the vast majority of listed asset managers having only small to medium-sized market capitalisations, thereby remaining off the radar of many equity investors. In the MSCI World Index, the financial industry has the second-heaviest weighting after the IT industry. Investors who adapt their strategic asset allocation to this index therefore invest in financial companies almost by necessity. However, it is very unlikely that investments will be made in publicly listed asset managers, since they constitute less than 4% of the MSCI World Financials Index, which specialises in the financial industry. In other words, Blackrock and Blackstone may be goliaths in the asset management industry – measured by their market capitalisation – but they and all other asset managers listed in the MSCI World Financials Index combined have an index weighting no greater than that of Bank of America, meaning one single bank. Applied to the broader MSCI World Index, the asset management industry also appears in only small numbers in global equity portfolios. However, this in no way corresponds to its economic significance. This discrepancy gives rise to a medium- to long-term strategic investment case for publicly listed asset managers as well as tactical investment opportunities, such as in the current drawdown phase.

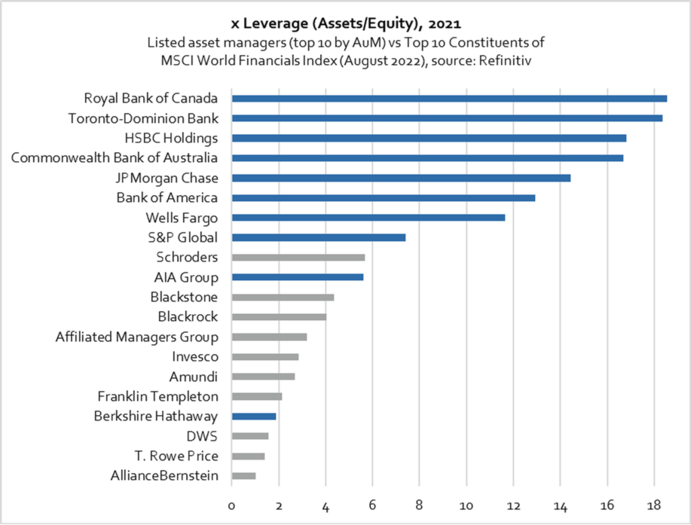

The founding of an asset management company requires far less regulatory capital than is the case for banks and insurers. Furthermore, asset managers resort much less to debt financing. Asset management is an “asset-light” industry. Asset managers tend to generate better total returns and returns on equity as well as stronger revenue and earnings growth.

They offer more growth and fewer value features than other financial companies, which also makes them ideal to diversify financial industry portfolios. The main risks for banks and insurers are losses of interest income, credit defaults as well as personal and property damages, while the main risk for asset managers is the capital market risk. Unlike banks, which engaged in – sometimes large-scale – own-account trading at least until the global financial crisis, asset managers by and large invest not as the principal, but as the agent, even taking into consideration hedge-fund and private-equity managers who invest their own money in the funds they manage. When the markets rise, the returns of asset managers rise. When interest rates rise, asset managers’ returns on fixed income funds fall, while the returns of banks rise due to improved interest rate margins – at least as long as increasing credit defaults don’t get out of control with the higher interest rates. Bank stocks performed better than the equities of asset managers when the interest rate cycle turned. The latter should find their way back to their relative strength as soon as inflation and a recession are priced into the broader market.

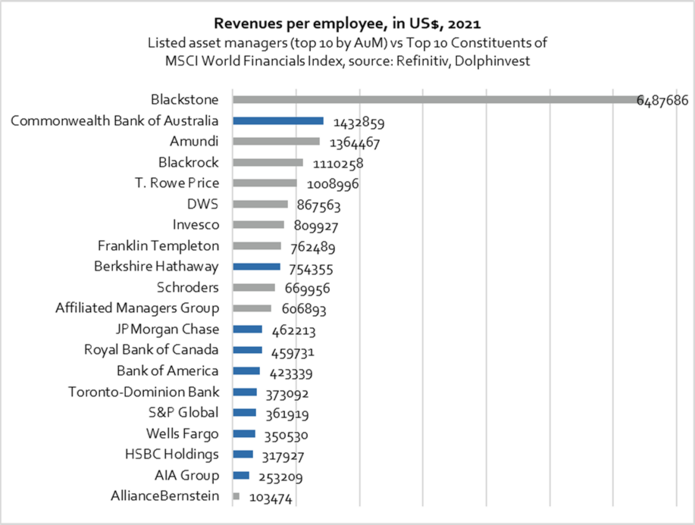

Historically, asset managers have outperformed both the broader equity market and the MSCI World Financials Index over the long term. From an investor’s point of view, strong arguments in favour of an investment in the equities of asset management companies include: (a) medium- to long-term capital-market growth and rising revenues for asset managers as a consequence;

(b) high beta and associated leverage on asset managers’ revenues; (c) high profitability per employee; (d) off-benchmark diversification effect; (e) growth potential for predominantly untapped client markets; and (e) demographic macro trends. At the end of 2021, the global equity market amounted to USD 124.4 trillion in market capitalisation, while the fixed income market had a value of USD 126.9 trillion in outstanding bonds. This compares with global assets under management – meaning professionally managed financial assets – amounting to USD 112.3 trillion, including USD 9.8 trillion in private markets (sources: SIFMA, Statista, McKinsey). Without taking into account money markets, asset managers therefore oversee at most 40% of all existing financial asset securities. Consequently, the market is far from being saturated. Asset management is – and will remain for the foreseeable future – a growth market, which will also be supported by a projected increase in the global population until at least 2065 and by rising demand due to an ageing population.

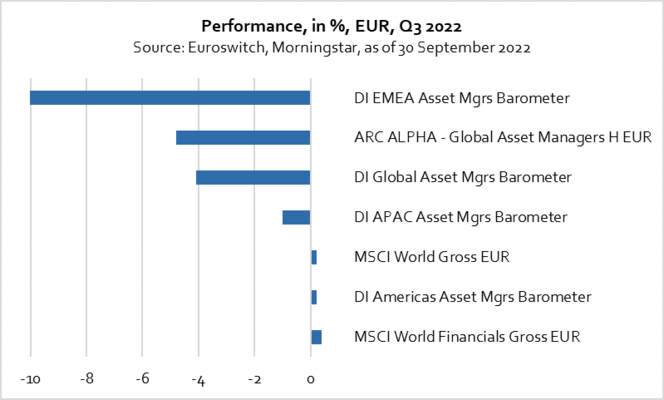

The year 2022 and the third quarter, in particular, have been difficult for the asset management industry. The Dolphinvest Global Asset Managers Barometer, which includes all publicly listed companies in the industry worldwide, ended the quarter with a decline of 4.1%. The ARC ALPHA Global Asset Managers is the world’s only globally equity fund which invests exclusively in listed asset managers. Its holdings comprise of a third of the 99 companies currently included in the Barometer. The fund posted a decline of 4.8% in the quarter, about five percentage points behind the MSCI World (in euros). The equities of European managers performed especially poorly compared with their peers from North America, Australia and Asia. The list of bad news for the European industry, in particular, is long: The European Central Bank has less room for maneuver than the US Federal Reserve does. The war in Ukraine and the destruction of real assets are in full swing and thus the situation in the energy market remains extremely tight.

The recession has arrived in the market. The destruction of financial assets through inflation is still under way, even though the signs of easing inflation are increasing. The relative underperformance of asset manager equities, compared with the broader equity market, started a year ago but has lost momentum in recent months. Nevertheless, we find it difficult at this point in time to be certain about a year-end rally for the industry. The peak of inflation and therefore of financial asset destruction will probably be reached soon. However, the depths of the recession are still ahead of us. But taking both aspects into consideration, we believe that a good time for a gradual entry into (or return to) the equities of publicly listed asset managers has arrived with the start of the current (fourth) quarter.

Frankfurt, 12 October 2022

For a more precise analysis and explanation, please contact Managing Partner

Michael Klimek

E-Mail: mklimek@dolphinvest.eu

Tel.: +49 69 339978-14

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Disclaimer: The "Dolphinvest Global Asset Managers Barometer" serves information purposes only. The data, comments and analysis reflect the opinion of Michael Klimek, Managing Partner at Dolphinvest, related to the markets and their trends on the basis of his own expertise, economic analysis and information currently known to him. They shall not under any circumstances be constructed as comprising any sort of offer. All potential investors should consult their service provider or advisor and exercise their own judgement independently on the risks inherent to each investment and its suitability to their own personal and financial circumstances.

What is the Dolphinvest Global Asset Managers Barometer?

Regularly we publish the “Dolphinvest Global Asset Managers Barometer“. This barometer is a tool for us to analyse the current situation of the asset management industry and to illustrate the view of international investors on the industry. For this reason, the “Dolphinvest Global Asset Managers Barometers’” publication is by no means a buy or sell recommendation.

The barometer displays the performance of more than 90 listed asset management companies in EUR. For inclusion in the barometer, it is a mandatory requirement that a minimum of 75 % of the overall revenue of a company is derived from asset management fees. Banks and insurance companies that have major asset management entities will, therefore, normally not be included in the index. The barometer represents all continents.

The transparency of listed asset management companies enables us to consolidate relevant information on the individual asset management companies included in the barometer into generally valid statements and to take them into account in our consulting work. Depending on the mandate, we divide the universe of constituents of the “Dolphinvest Global Asset Managers Barometer“ into groups of similar companies against which we then benchmark our clients.

For a more detailed analysis and an interpretation of the findings, please contact:

Michael Klimek

Email: mklimek@dolphinvest.eu

Phone: +49 69 33 99 78 - 14