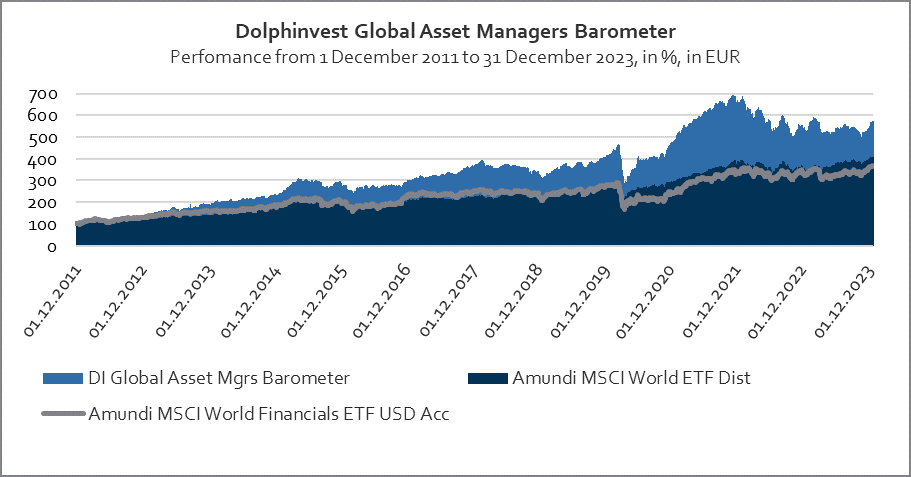

Dolphinvest Global Asset Managers Barometer

Growth through acquisitions

BlackRock CEO Larry Fink explained in an interview at the beginning of October that he is striving for further growth for his company through corporate acquisitions and is particularly interested in specialists in private capital markets. Why is that?

BlackRock emerged in the 1990s as a spin-off from Blackstone. What followed was a meteoric rise. The company grew organically, but also through strategically important acquisitions. No other asset manager in the world manages more client funds than BlackRock, which earns its money primarily from passive – but also active – investments in equities and bonds, meaning in public markets.

Blackstone, on the other hand, specialises in private markets – from real estate to private equity. Even though Blackstone manages less client money than BlackRock, it is the larger of the two successful companies based on market value.

Picking the neighbour’s cherries

Fund managers in private markets, like Blackstone, can charge much higher prices for their services and products than their colleagues in equity and bond management. Declining inflows, increased costs and additional regulatory requirements have forced the hand of many traditional asset managers. They don’t have many courses of action: Either they lower their prices and work more efficiently, using new technologies, for example. Or they increase their revenues by adding premium products to their range, with which they can cross-subsidise their lower-priced products, if necessary.

Traditional asset managers are therefore peering enviously at the other side of the market, which may also be the motivating force for Larry Fink’s publicly declared desire for acquisitions. The prospect of earning fees at triple-digit basis-point levels – which are common practice in private markets – is very enticing. Anything would seem possible if an uncertain economic outlook and possibly more interest rate increases didn’t complicate the decision – both on the buyer’s side and the seller’s side.

Two worlds

However, private and public markets also display distinct structural differences. In both markets, capital-seeking enterprises are matched with capital providers. But investors are active in public markets only on the day of a company’s initial public offering and during any capital increases. This means investments almost never take place in equity and bond markets – instead securities just change owners for the most part. The highly efficient public markets make it possible to change owners literally every nanosecond.

Private markets are different. Here, investors invest directly in companies. The target companies receive capital that they can use for their business activities. But the private market’s liquidity is – unlike that of the public market – limited. The secondary market for venture capital and private equity investments doesn’t even come close to the liquidity of the equity markets. The purchase of a private company shareholding is a bureaucratic act that involves differing costs and procedures depending on the country and, for example, requires an appointment with the notary.

On the other hand, the advantages of an investment in private markets – besides the opportunities – include historical returns that have often been more attractive than those in public markets.

Under the spotlight

Another disadvantage of public markets, according to some market participants, is that listed companies frequently have a much larger circle of stakeholders to service. As a result, they frequently have to justify their decisions and activities, not just to their shareholders, but also to the public at large. In the US, the pressure that was recently applied to asset managers like BlackRock, both by ESG advocates and ESG critics, was immense and could only have been disadvantageous for the companies affected. BlackRock’s Larry Fink, for example, felt obliged to announce that he no longer uses the term ESG.

Private markets receive additional momentum from legislative and regulatory developments. Against the backdrop of the global financial crisis 15 years ago, authorities in the US and the European Union began to make it easier for private investors to access private equity funds that were previously available only to professional investors. In the US, retail investors are now allowed to subscribe to closed-ended funds within the framework of 401(k) retirement schemes. In the EU, the new fund vehicles EuVECAs and ELTIFs were created to reduce the relatively high dependence on banks – compared with the US and UK – in corporate financing. This was part of the EU’s plan to establish a capital market union.

The rationale is coherent. Instead of governments asking all taxpayers to foot the bill whenever a banking crisis threatens a major firestorm and requires bailout, it seems more sensible to prevent crises by spreading corporate lending to shoulders that are much more independent of one another and, most importantly, have no systemic relevance – the shoulders of taxpayers, that is, private investors. For the assumed investment risk, they are rewarded with attractive returns and enhanced wealth accumulation.

The result is a win-win situation for the state and its citizens that also attracts fintech enterprises. They sense business for innovative settlement platforms that facilitate investments in unlisted companies and to trade shares in venture capital and private equity companies. This is beneficial for the overall liquidity of the private market. The tokenisation of shares in unlisted companies has already begun.

Industry in crisis

This auspicious environment has been disrupted by the Covid-19 crisis, the war in Ukraine, inflation and the interest rate reversal, with economic challenges coinciding with central bank policy that sometimes appears overwhelmed. One thing is clear: The days of ultra-cheap money are over. The financing of an acquisition is becoming more expensive as a result. How does the capital-intensive feat of a company takeover pay off? With rising interest rates, the markdowns on future returns are getting larger, which is squeezing valuations. Against this backdrop, are any willing sellers to be found at all? How can business development planning work amid the currently huge uncertainty?

Based on the run rate at the end of August 2023, we indeed expect overall transaction numbers to fall below the level of the previous two years, and estimate the average volume of assets under management at USD 6 billion per transaction. While this figure is 50% higher than in the previous year, it is much lower than during the years 2021 and 2020 (USD 8.4 billion and USD 11.4 billion, respectively. Source: Piper Sandler) and can be interpreted as a declining medium-term trend. The No. 1 reason for the decline in transaction numbers and volumes is: Traditional asset managers find themselves in a continuously declining five-year trend, with the demand for them reaching absolute rock bottom this year.

By contrast, there is the segment of wealth managers specialising in private clients. Their share of total transaction numbers has risen steadily from 55% (2019) to 76% (2023). They are, by far, the most common M&A target in the industry. However, the average AuM volumes for takeovers of wealth managers are comparatively low. This is the No. 2 reason for the declining trend in transaction volumes.

Apart from wealth managers, alternative asset managers remain popular takeover candidates this year, albeit less so than in the past two years. Based on transaction numbers, traditional and alternative asset managers were neck and neck with each other from 2019 to 2021 but drifted apart in 2022 and 2023 in favour of the alternative managers.

Firstly, we believe the strong demand for takeovers in the wealth management segment will not change markedly any time soon. Without direct – even if it’s digital – contact to retail customers, private market funds that need explanation, like ELTIFs, cannot be sold widely. But traditional asset managers without own direct distribution resources also rely on wealth managers as a sales channel.

No quick comeback

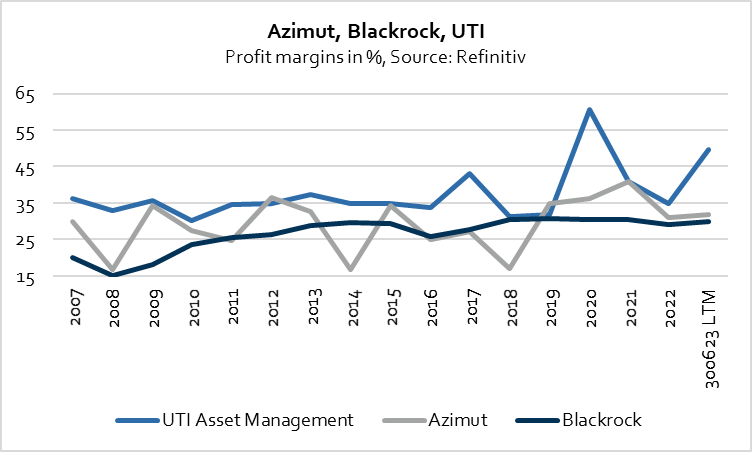

Secondly, we consider it unlikely that traditional asset managers will become popular takeover candidates again in the coming months – except for target companies that operate in markets where high fees are still enforceable or where profit margins are high due to low staffing and other costs. India is one example of such a market.

Thirdly, we see the competitive advantage of private versus public markets. Advantages include a greater number of investment opportunities, greater potential for returns with improving liquidity and, not least, the political will to democratise the private market and transfer state tasks to it. The tasks extend from the financing of middle-market companies – which is often the responsibility of state-backed development banks, besides the principal banks – through to the financing of the green transformation of the economy, as well as investment in traditional and innovative infrastructure at local, state and federal levels.

Fourthly, we therefore consider it likely that takeovers of alternative asset managers will continue to appear attractive, but we note that many of the larger ones have already taken on external shareholders. Two years ago, the share of private equity managers that oversaw more than USD 15 billion in client funds and had “GP stakes” investors as shareholders, already stood at a remarkable 42.4%, with the trend pointing upwards thanks to unabated interest (just look at Larry Fink).

Publicly listed asset managers

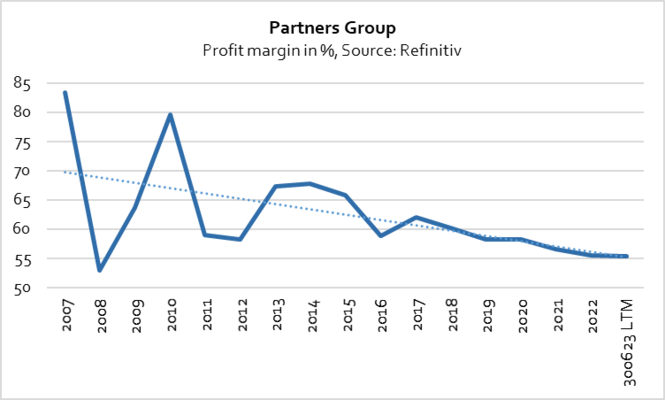

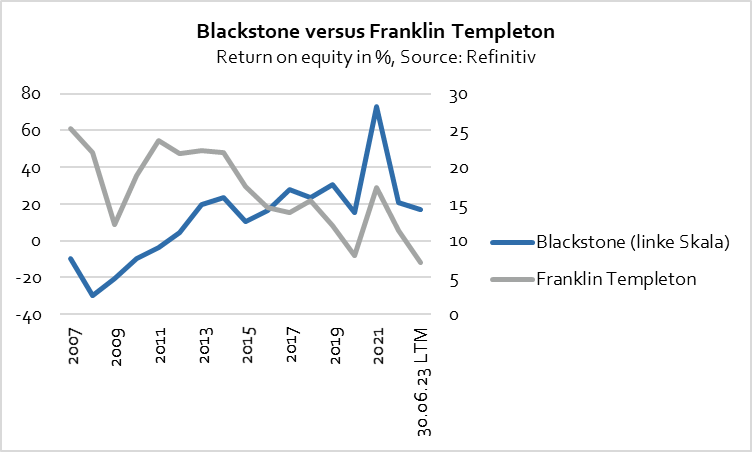

The shares of publicly listed asset managers, which are predominantly traditional asset managers, have been lagging the broader equity market for about two years. The industry’s average return on equity (ROE) and profit margin are at the lowest levels in 12 and 14 years, respectively. And yet, optimists could argue that this hasn’t spoiled the long-term average of 16% for return on equity and 20% for profit margin, and the wavelike ups and downs of return on equity and profit margins in the past provide hope for an imminent upswing.

The market is certainly anything but homogeneous, and the competition is accordingly broad. While alternative asset managers can often stand out from the competitive environment, they aren’t immune to margin erosion, for example, albeit at a high level.

Furthermore, with Blackstone, an alternative asset manager has shown rising but surprisingly below-average returns on equity in the past and moderate returns at best in the present, while the traditional asset manager Franklin Templeton dropped from above-average (2007) to clearly below-average (2023) in the same period.

The often-claimed theory that the pressure on margins has indeed led to margin erosion – especially in the segment of traditional asset managers – cannot be generalised, as three examples from Europe, Asia and the US show:

In high demand despite crisis: Alternative asset managers

In the third quarter of 2023, the industry’s underperformance compared with the overall financial sector, as well as the broader equity market, continued. The sector fund ARC ALPHA Global Asset Managers was able to end the third quarter satisfactorily compared with the asset management industry overall (represented by the Dolphinvest Global Asset Managers Barometer). The fund turned in a slightly positive performance (after costs), while both the average and the median of the 103 individual companies in the Dolphinvest Global Asset Managers Barometer posted a negative performance (-0.85% and -0.93%, respectively, before costs).

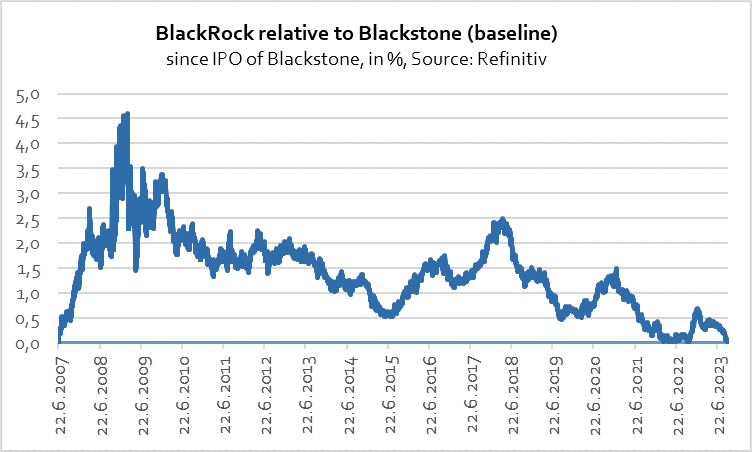

The performance contribution of alternative asset managers was significant. Since the beginning of the year, they have accounted for six of the top 10 performers in the barometer, or even eight of the top 10 in the third quarter. Since the year began, Blackstone has posted a gain of +46.2% (until the end of the third quarter, based on euros) and +18.9% in the third quarter. In the same periods, the fund returned +0.05% and +1.48%, respectively, while BlackRock disappointed its shareholders with declines of -8.8% in the year to date and -6.5% in the third quarter.

For years, the relative performance advantage of BlackRock shares versus Blackstone shares has dwindled ever further, until it finally came very close to the baseline this year. If it is true that the future is traded on the stock exchange, then the need for action may indeed have intensified from the perspective of Larry Fink.

Frankfurt, 17 October 2023

If you have any questions, please contact:

Michael Klimek

E-Mail: mklimek@dolphinvest.eu

Tel.: +49 69 339978-14

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Disclaimer: The "Dolphinvest Global Asset Managers Barometer" serves information purposes only. The data, comments and analysis reflect the opinion of Michael Klimek, Managing Partner at Dolphinvest, related to the markets and their trends on the basis of his own expertise, economic analysis and information currently known to him. They shall not under any circumstances be constructed as comprising any sort of offer. All potential investors should consult their service provider or advisor and exercise their own judgement independently on the risks inherent to each investment and its suitability to their own personal and financial circumstances.

What is the Dolphinvest Global Asset Managers Barometer?

Each quarter we publish the “Dolphinvest Global Asset Managers Barometer”. This barometer is a tool for us to analyse the current situation of the asset management industry and to illustrate the view of international investors on the industry. For this reason, the “Dolphinvest Global Asset Management Barometers’” publication is by no means a buy or sell recommendation.

The barometer displays the performance of more than 100 listed asset management companies in EUR. For inclusion in the barometer, it is a mandatory requirement that a minimum of 75% of the overall revenue of a company is derived from asset management fees. Banks and insurance companies that have major asset management entities will, therefore, normally not be included in the barometer. The barometer represents all continents.

The transparency of listed asset management companies enables us to consolidate relevant information on the individual asset management companies included in the barometer into generally valid statements and to take them into account in our consulting work. Depending on the mandate, we divide the universe of constituents of the “Dolphinvest Global Asset Managers Barometer” into groups of similar companies against which we then benchmark our clients.

For a more detailed analysis and an interpretation of the findings, please contact:

Michael Klimek

Email: mklimek@dolphinvest.eu

Phone: +49 69 33 99 78 - 14